Should I Shift to Dividend Stocks As I Get Closer to Retirement?

The first stock I ever owned was a local utility called Long Island Lighting Company, which paid a healthy dividend. My Dad gave me a few shares of LILCO when I was a kid to teach me about investing, and I still remember the delight of receiving those $10 dividend checks every 3 months.

While it’s easy to understand why many do-it-yourself retirees and advisors recommend dividend stocks, it’s not the best wealth-building strategy. The bottom line with focusing on dividends is that it comes with risk, there are misperceptions about the benefits, and there are better ways to grow wealth and generate income in retirement.

Focusing on Dividends Comes with Risk

Given that some industries pay more dividends than others, you end up concentrating in certain sectors of the market, like utilities and energy, which adds risk that you’re not compensated for. A downturn can really hurt a portfolio of dividend stocks.

Dividend stocks also tend to have greater interest rate sensitivity than other stocks, making their performance more susceptible to changes in rates. For example, high-dividend stocks can lag the market when interest rates rise. One study showed that when rates rose the most, high dividend stocks had a 4.2% shortfall relative to the market that same year on average.

Dividends Don’t Come Free

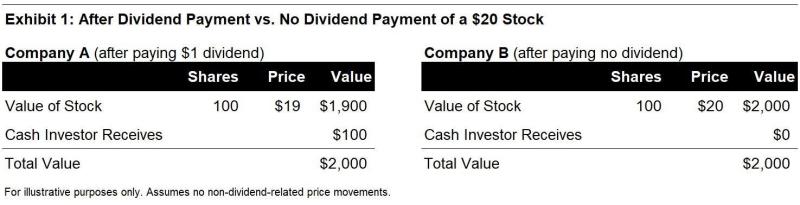

There’s a misperception that higher dividends help a retiree avoid encroaching on capital to generate cash flow, and you’re better off receiving dividends than dipping into principal. What many investors don’t realize is that the value of a stock drops by the amount of the dividend you receive. For example, consider two companies that are identical, except one pays a dividend and one doesn’t.

Because the stock price of Company A is automatically adjusted downward by $1, the value of the stock is reduced, and total wealth is not affected by a dividend payment. But that’s before taxes.

Dividends Are Tax Inefficient

When considering after-tax returns, an investor is usually better off selling stock than receiving a dividend, all other things being equal. That’s because dividends are taxed in their entirety, while only the portion that represents a gain is taxed in a stock sale.

To illustrate, let’s assume that both companies were purchased at $16 per share, and dividends and gains are taxed at 15% (at the time of writing qualified dividends and long term capital gains are taxed at the same rate).

High tax rates have made dividends even less favorable in the past. While currently 15% to 20% for qualified dividends, at times dividends have been exempt from taxes, but at other times they were taxed at the individual’s income tax rate up to 90%!

There are additional benefits of “self-creating” cash flow by selling securities in the portfolio that go beyond after-tax returns. You have greater control over the level and timing of distributions. So say you spend less that you anticipated and don’t need the income for a given period, you can forgo selling shares and avoid the tax obligation. You can also pick which assets to sell, and use those sales for things like tax loss harvesting or to rebalance your portfolio back to its target allocation.

Dividend Stocks are Not Bonds

A common mistake investors make is substituting dividend stocks for bonds, with the idea that high dividend stocks provide yields that are near corporate bonds, but offer appreciation and lower taxes. This all may be true, but it’s not the whole story.

Shifting from bonds to dividend-paying stocks significantly raises a portfolio’s risk profile and diminishes its downside protection. For example, when the COVID pandemic rattled markets in the first quarter of 2020, high-dividend stocks fell by 24% while bonds rose 3%. It’s important to remember that the role of bonds is to serve as a ballast in a portfolio when stocks are volatile, and shifting to dividend stocks defeats that purpose.

There Are Better Uses of a Company’s Capital

Economists have a hard time explaining why companies even pay dividends in the first place. If you think about it, paying out dividends to shareholders isn’t the best use of capital from a business standpoint. If a company instead redirected those earnings to things like R&D, product innovation, marketing or acquisitions, it should be in a better position to grow earnings more quickly. And if earnings grow more quickly, shareholders should benefit from a more rapidly growing share price.

Just ask Warren Buffett. Berkshire Hathaway paid out a dividend just once under Buffett's watch; a 10-cent-per-share payout in 1967. Buffett later joked "I must have been in the bathroom when the decision was made." Even though Berkshire’s shareholders have been asking for a dividend for years, he’s stuck to his guns by reinvesting in Berkshire’s business or buying back Berkshire’s stock when it’s cheap. In one of his letters to shareholders, he even goes into great detail about why a share “sell-off approach” to generate cash is better for both the company and its individual shareholders.

Dividend Stocks Are an Indirect Way of Owning Value

Investors often point to historical data that shows dividend-paying stocks have outperformed the average stock. That’s true, but dividends aren’t the driving factor. Dividend stocks are often what we call value stocks, or stocks that are cheap relative the company’s earnings or book value. And research suggests that it is the value factor that has driven this outperformance, and that dividend yield is just an indirect way gaining exposure to value.

What’s more, stocks that pay dividends actually detracted from the performance of value stocks, and avoiding high-dividend stocks has produced better returns in a value strategy on an after-tax basis as shown by Meb Faber. Faber concludes that the only time you would ever want dividend stocks is in a tax-exempt account, and even then you should prefer value.

An Alternative Approach: Focus on Total Return

A total return approach focuses on building a portfolio that seeks greater long term investment growth, and takes into account returns stemming from both income and capital appreciation. Its objective is to produce greater wealth and a steadier amount of income over the long run relative to a focus on dividends and income.

Sometimes you don’t have to touch your investment principal with this approach. If dividends and interest from your portfolio along with other income sources are enough to support you in retirement, great. If not, you can fill the gap by selling securities in the portfolio. This way you’ll have greater control over the level and timing of distributions, rather than letting portfolio yields determine spending rates, and potentially have more wealth in retirement.

Conclusion

It’s easy to understand why investors might instinctively want to shift towards dividend-paying stocks in retirement, especially in times of low interest rates. This approach can work out fine, just as it did for many of our parents and grandparents. However, it’s important to understand that dividends are just another source of profit along with capital gains, and that focusing on high-dividend stocks comes with risks and potential drawbacks. Instead, a total return approach that incorporates yield, price appreciation and tax efficiency can provide better outcomes for retirees.